Below is an expaination of the concept of reihō.

While there are some differences from what we practice at our dojo,

hopefully this will give some insight into the core principles of all martial

arts. Courtesy and respect must be integrated into your study of

karate-do. O Sensei Dr. Tsuyoshi Chitose, founder of Chito Ryu,

tells us that "Without courtesy, the soul is lost."

Note: My apology to the original author for

not giving proper attribution. The source information could not be

located.

The meaning of reihō can be sometimes

translated as "etiquette," "respect" or

"courtesy." It is a very important concept in Japanese culture,

including traditional Japanese martial arts. It is not a "ceremony"

or a "ritual" per se; as this may construe that it is performing an

exotic spiritual or religious act without meaning, which is not the case. In

Japan this act is considered ancestral reverence. While reihō may have

the meaning of "etiquette," this does not adequately describe its

many connotations.

Reihō is in many ways a code of conduct, which in Japan is applied to

one's everyday life. For example; at school, at work, at home, when they visit

their doctor, ect. In Japan "rei" is not taught to the

Japanese – usually only to foreigners – because it is generally known due to

its culture. In our western culture (specifically American) we tend not to

"show respect." And when we do give respect we often express it by

saying it. And when we do say that we respect someone as in "I respect you"

it is seldom given out. So, reihō is a foreign concept to westerners.

Since we are dealing with a Japanese martial

art, reihō is included in the Genbukan. It is the basis of all

traditional Japanese martial arts, no matter what their roots are. Without reihō

in martial arts it would be nothing more, nor better, than hoodlums

fighting in the streets. In the Genbukan the purpose of reihō has

two purposes. First, it is a way of paying respect to the tradition, the

teacher, and the students. Secondly, it provides a degree of safety, especially

during the use of weapons. In the Genbukan, as well as most Japanese

martial arts, everything begins and ends with reihō.

Entering the Dōjō

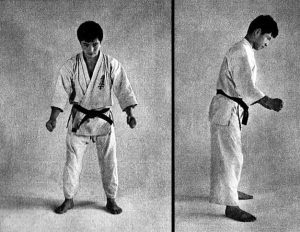

When entering the dōjō, stand in a

natural posture and perform shizen rei (standing bow) to anyone present,

and say one of the following: ohayō gozaimasu (good morning), konnichiwa

(good afternoon), or konbanwa

(good evening). If you are already at the dōjō it is customary to

stand up and greet the teacher when he arrives.

Entering and Exiting the Training

Floor

Before entering on the training floor, face

towards the kamidana (dōjō shrine) and perform shizen rei.

If you are training outside you will face to the north and perform shizen

rei.

Note: If you are late to class, quickly prepare yourself for training.

Upon entering the dōjō, immediately step off to the side and perform the

shinzen rei.

Beginning and Ending of Class

The beginning and ending of class is

signified by a formal bowing consisting of two parts: shinzen rei (bow

in acknowledgment of the tradition) and shi rei (bow to the teacher).

1. Beginning: Seiretsu – Form

a line

At the beginning of class the instructor will

say, "Dewa keiko wo hajimeru" (begin training). Thesenpei (the

senior) will command everyone to line up in a row by saying, "Seiretsu!"

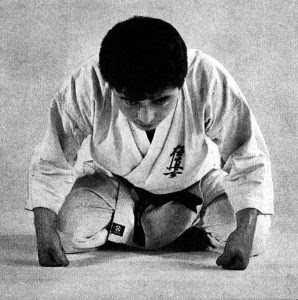

All the students will line up by rank and kneel into seiza (a seated

posture) with the senpei at the lead, facing the kamidana (dōjō

shrine). The instructor will move to the front of the class and kneel into seiza

facing the class.

2. Mokusō – Meditation

The senpei will then instruct everyone

to perform mokusō (Japanese term for meditation to "clear one's

mind"). Everyone will then place their hands in their laps, right hand

over left, thumbs touching, and then lightly closing eyes to clear their minds.

After a few minutes, the instructor will then recite the "Ninniku

Seishin" poem with everyone following his lead. The instructor will

then stop the meditation by saying "Mokusō yame." Everyone

will then open their eyes and places their hands on the thighs.

3. Shinzen Rei – Bow before

the shrine

The instructor turns around and faces the kamidana

(dōjō shrine). He then places his hands ingasshō (hands

together in front of his chest). The students with then follow his lead by

doing the same gasshō. The instructor then recites the following phrase,

"Chihayafuru kami no oseiwa tokoshieni tadashiki kokoro mi wo

mamoruran." (The teachings of God never changes throughout eternity

and will protect you if you have a correct mind/heart/spirit). And then he

says, "Shikin haramitsu daikōmyō!" (The sounds of words in our

reach for perfection will lead us to the powerful light). The students then

repeats, "Shikin haramitsu daikōmyō!" Everyone then claps

twice, performs a bow, and claps one more time followed by one more bow.

Note: If the Teacher is not in class then the senpei does NOT go

to the front of class where the teacher sits. He stays in the usual place at

the far right.

4. Shi Rei – Bow to the

teacher

The instructor then turns around and faces

the class. The senpei will command everyone to correct their posture and

bow to the teacher by saying "Shisei wo tadashite, Sensei ni

rei!" The students then bows to the instructor, while the instructor does

the same to the students, with everyone saying, "Onegai shimasu."

(Please assist me).

Note: if the teacher is not in class, the the senpei says “Shisei

wo tadashite, shinzen ni rei!”

5. Ending: Seiretsu – Form a

line

At the end of class the instructor will say,

"Keiko owari" (Training has ended). The senpei (the

senior) will command everyone to line up in a row by saying, "Seiretsu!"

All the students will line up by rank and kneel into seiza (a seated

posture) with the senpei at the lead, facing the kamidana (dōjō

shrine). The instructor will move to the front of the class and kneel into

seiza facing the class.

6. Mokusō – Meditation

The senpei will then instruct everyone

to perform mokusō (Japanese term for meditation to "clear one's

mind"). Everyone will then place their hands in their laps, right hand

over left, thumbs touching, and then lightly closing eyes to clear their minds.

After a few minutes, the instructor will then stop the meditation by saying

"Mokusō yame." Everyone will then open their eyes and places

their hands on the thighs.

7. Shinzen Rei – Bow before

the shrine

The instructor turns around and faces the kamidana

(dōjō shrine). He then places his hands ingasshō (hands

together in front of his chest). The students with then follow his lead by

doing the same gasshō. The instructor then recites the following phrase,

"Chihayafuru kami no oseiwa tokoshieni tadashiki kokoro mi wo

mamoruran." (The teachings of God never changes throughout eternity

and will protect you if you have a correct mind/heart/spirit). And then he

says, "Shikin haramitsu daikōmyō!" (The sounds of words

in our reach for perfection will lead us to the powerful light). The students

then repeats, "Shikin haramitsu daikōmyō!" Everyone then claps

twice, performs a bow, and claps one more time followed by one more bow.

Note: If the Teacher is not in class then the senpei does NOT go

to the front of class where the teacher sits. He stays in the usual place at

the far right.

8. Shi Rei – Bow to the

teacher

The instructor then turns around and faces

the class. The senpei will command everyone to correct their posture and

bow to the teacher by saying "Shisei wo tadashite, Sensei ni rei!"

The students then bows to the instructor saying, "Arigatō gozaimashita."

(Thank you). The instructor bows to the class while saying, "Gokurō

samadeshita" (thank you very much for your efforts). The senpai will

then give a command to the students to bow to each other by saying, "Sōgo

ni rei." Everyone will then bow to each other and says "Arigatō

gozaimashita."

Note: if the teacher is not in class, the senpei says "Shisei

wo tadashite, shinzen ni rei!"

Exiting the Dōjō

Upon leaving the dōjō, stand in a

natural posture and perform shizen rei (standing bow) and say one of the

following: oyasumi nasai (good night), or shitsurei shimasu (pardon

me leaving).